“A still photographer has to show the whole fucking movie in one picture”

It was January 1992 and I was driving upstate in New York. Everything was fairytale white and it was still snowing quite hard when I arrived at Eddie Adams’ hideaway. I drove past a typical American barn - which I learned later housed his studio, workshops, guest bedrooms and darkrooms. I pulled up before a beautiful farmhouse.

I had interviewed so many war photographers who had similar places of solace tucked away in the countryside. George Rodger, one of the four founders of Magnum, one of the first photographers inside the liberated Bergen Belsen concentration camp … George made those harrowing but iconic images of the starving inmates in their striped pyjamas. Ian Berry, who recorded the Sharpeville massacre after the armed white apartheid police thought they had evicted all the press, and was nearly killed himself. Don McCullin who was prevented by Maggie Thatcher from covering the Falklands War – after all, it was a godsend to her re-election campaign - the last thing the Iron Lady needed was McCullin’s negative images of war appearing in the press.

All these photojournalists, and there are many others, had escape holes - places of solitude tucked away in the countryside.

A Harley Davidson parked outside was rapidly converting into an expensive snow sculpture. I banged on the kitchen door. I was greeted by Alyssa – Eddie’s wife – and a waft of hot air mingled with the yummy savory, tangy and sweet aroma of spaghetti sauce. A long kitchen table with a scrubbed pine top had been set for a dozen diners. A mishmash of plates and cutlery, odd chairs, tin mugs, wine bottles were assembled. Another women stirring the contents of a huge cooking pot was humming a well known country melody.

Smiles from both of them. “You must be Peter?” said Alyssa, “Eddie’s in the back room… would you like a hot drink?

I could hear the sound of a piano being tuned.

Two Rip-van-Winkles appeared in the doorway, long beards down to their nuts. Behind them Eddie Adams wearing his landmark trilby. According to Alyssa, Eddie’s trilby was a permanent fixture “Even in bed” she added! Eddie smiled and said: “These two guys came up for Woodstock Festival and never left. Now they’re the unofficial caretakers of all the Woodstock memorabilia and museum.”

The Rip-van-Winkles said nothing, nodded and left.

Eddie indicated I should follow him.

I gingerly stepped over a conga line of toy trucks and cars that seemed to wind their way from the kitchen, down the hallway and out of sight beyond. We passed an upright piano and a not so upright piano tuner - his head buried in its interstice – a tuning fork waved at us and carried on tuning. “A friend of the Nonna” I was told as I followed the toys into the back room.

Someone called Sam was standing, legs akimbo, in front of a roaring log fire, toasting the arse of his wet leathers. I was introduced, obviously to the owner of the snow-covered Harley Davidson. I mentioned the snow and Sam left to cover his hog.

A smell of warm damp leather pervaded the room.

“I’m not a great believer in the power of the moving image”, said Eddie, avoiding a miniature gas station at the start of the conga-line in the middle of the floor, before dropping into his favourite armchair.

“A still picture has greater lasting power. A still photographer has to show the whole fucking movie in one picture. On the screen, it’s over and back in the can in seconds. A still picture is going to be there for ever.

“And incidentally, I have no intention of talking about that image!”

He did of course.

Later.

I said nothing.

Sometimes it’s better to just listen.

“It’s easier with movies. With film you can do anything. I mean,

You have sound working for you. you have movement. You have the passage from dark to light, you have... I’ll tell you an interesting story, during the war in Vietnam, Larry Burrows and I did the first sound film in Vietnam for CBS - a one-hour documentary. (Larry, together with three other photographers, was killed in Laos in 1971 when his helicopter crashed.)

“When I first went to Vietnam, CBS only had 16 mm silent cameras - this was long before video cameras came onto the scene.

“Larry and I went to CBS headquarters where they were showing our sound documentary after the sound had been mixed in.

“A Viet Cong prisoner being questioned. Anyway, at one point the interviewer slapped this guy in the face, and Larry and I looked at each other and said “did you hear that?” - I mean the impact of the sound of that slap was startling!

“Larry turned to me and said “we might as well throw our cameras away – sound has come to the war”.

“We were totally freaked out.

“It was such a fucking shock hearing that sound because everything up to then had been silent. Yet, that slap has been heard in many still photographs as well. A lot of times you go out on a battle assignment and there’s all kinds of bullets flying around and you’re too terrified to stick your head up. I mean, what’s your picture going to be? Some guy hiding behind a fucking tree?”

“But point a movie camera at the same guy behind the tree and the sound tells you what's going on - the danger, the feeling of terror, the futility of it all. It’s not the same with a still camera. A stills picture of the guy behind the tree may just be a photo of a man and a tree. A still picture needs a whole lot more. In all successful war photographs you can hear the sound of the explosions and the screams of people dying.

“The difference between a stills photographer and a movie photographer is that in the tiny amount of time the stills photographer has - maybe it’s only one-five-hundredth of a second … you know his image, frozen in celluloid, is going to live on in people’s memories in the photograph for the rest of their lives - even though the soldier’s life is going to be over in a fraction of a second.”

So many still photographers and journalists, go into battle because in the beginning it all seems exciting … like a Boy’s Own adventure… but they learn very quickly that the reality isn’t like that at all. They soon discover that the wealthy people have gotten on their planes and boats and left the war zone. Its always the poor people that get caught in the crossfire.

Take a look at Gaza today.

“I’ve been asked many times, ‘Why did I want to photograph wars?’. Well, it wasn’t because of the excitement - although there are several war photographers - like Don McCullin - who got into it for just that reason.

“Well, I certainly didn’t want to die!

“I mean, I’m not afraid to die. But I don’t want to die for no reason.

“I don’t know what attracts me to those situations. For example, I was in Kuwait and Iraq for about a week for Life Magazine when the shooting started and I told Life I wanted nothing to do with it - because of the bullshit of censorship. The war was being played out on the editor’s desk. It was like Hollywood, and why get killed for a fucking movie?

“So, the day the first bullet was fired and the ground war started, I asked to leave, I said I’m too old for this. I don’t want to do it. And that’s a different frame of mind for me.

“Maybe, I realised my time was up.

“I’ve been there too many times before.

“I was there during the Iraq/Iranian war with an NBC crew. The sound man, who was less than six feet behind me, had his arm ripped off and the producer ended up with a big chunk of shrapnel in his body and yet was OK. Well, I started to ask myself, what the fuck am I doing here when I don’t need to be?”

I asked Eddie, if he was retiring from war photography, what was more important to him now?

“I’m more interested in that now, than I am in war” Eddie pointed to his three year old son arranging the conga line. “I got married again. I’ve got a baby now - well, I’ve had babies before - I have kids who are adults who are married - with kids of their own - and I hardly know them. I was never there to watch them growing up, and I want to know this one a little better - I left them all to go and play war games.

“What for?

“Why?

“For the sake of a few lousy pictures that will never tell the full truth because of the censors?

“There’s so much bullshit associated with war photography, the least of which is what the editors and censorship drones do with the pictures they receive. For example, during the Vietnam War Associated Press had pictures of 173rd Airborne, standing in a line for a group picture, holding up all these severed heads of dead Viet Cong by the hair - like ‘trophies’.

“Nobody saw those pictures.

“Hell – The marines were supposed to be the good guys. Well, we photographers didn’t want to take the responsibility of radioing these pictures back to America - because everything was monitored in North Vietnam. Any pictures that we moved on the wire, they’d pick up in the North, and use for their own propaganda purposes. These pictures were too sensitive, and here’s American special forces whooping it up like Geronimo.

“So we mailed the original negatives to the President of the Associated Press in New York. They were never published. They were all thrown into the incinerator. You see, officially our guys don’t commit atrocities. We’re Americans, we were supposed to be the good guys.

“These days, I edit my pictures all the time, sometimes before I take them. This is bad, because a lot of times I don’t take the pictures I should and that’s what I’m getting paid to do. Maybe, it’s because I’ve seen it all before. Maybe I’m not an objective reporter anymore. Maybe I think it’s all bullshit and no matter what I photograph, somebody else is going to lie about it anyway.

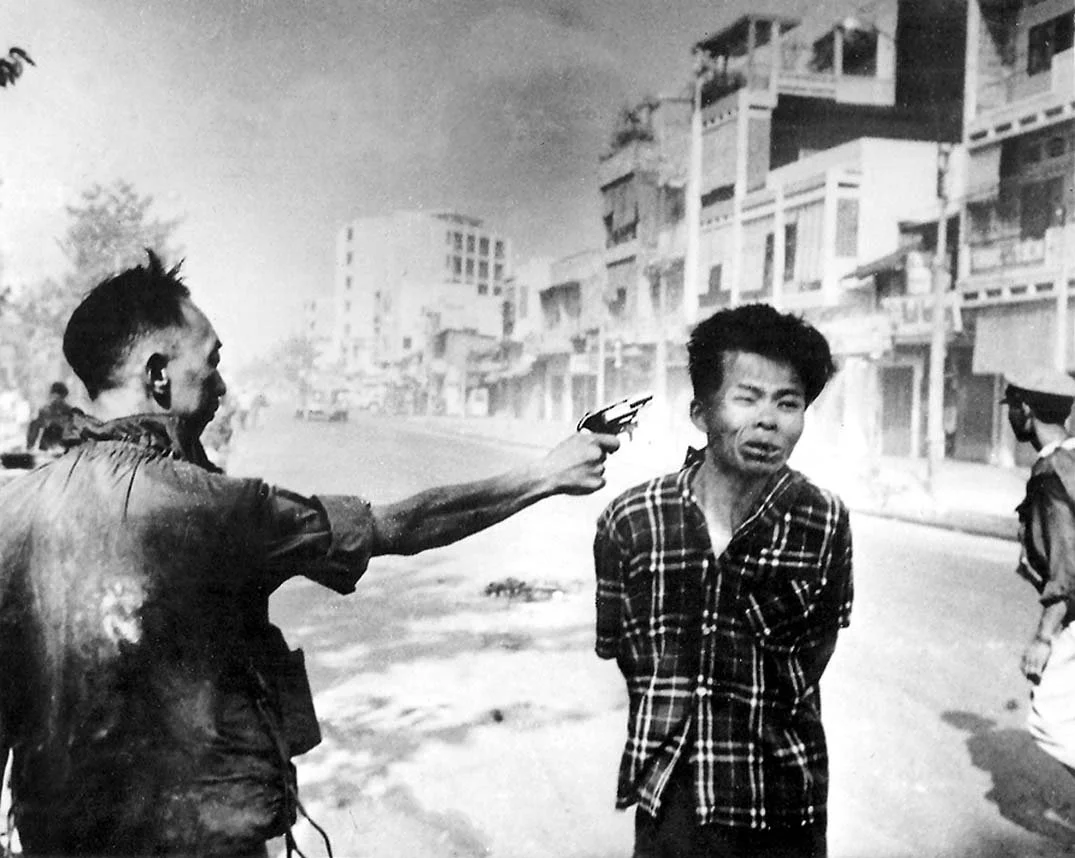

“Knowing what I know now - if the Vietnamese general (In my photo) was going to shoot the Viet Cong guy in the head, would I take that photograph now? Well, I probably would. I would probably take the fucking picture again. And it would probably get abused again by all those picture editors and government drones trying to make a buck by pedalling their magazines.

“These days magazines can’t be trusted to tell the truth like they once did. Magazines like Picture Post and Paris Match, used to have six or seven pages dedicated to the story relating to an image or a series of images. These don’t exist anymore.. Now it’s all controlled by advertising - advertisers don’t want to see blood and guts next to their boxes of washing powder.”

Eddie’s Vietnam picture was exploited and abused in the USA.

Of course he wasn’t there, so he couldn’t defend it. He was still in Vietnam. The image came back to the States and was used all over the place in anti-war stories. Photographs without words can be misinterpreted in so many different ways. The same photograph with a few words, is far more accurate. And the story behind Eddie’s image was never told.

“I mean, during all the anti-war demonstrations it was used on big banners saying ‘It’s their war and not ours. Let them fight it’. And as for the poor guy? Well, I’ll give you some background on him.

“After the war, General Nguyen Ngoc Loan escaped to the States (1975). He had a restaurant ‘Les Trois Continents’ in Virginia and I went to visit him and I got to know him really well. It was funny, I walk into his shop and I see him standing behind the coffee counter making cappuccinos.

“It was bizarre. Here’s a guy, a general, who was trained at West Point, who came first in his class in at Atlanta staff college, and a graduate of école de l’air et de l’espace (French Air and Space Force Academy) who flew helicopters. This guy was no dummy - and here he was making coffees. So, I walk into his pizza shop - he sees me coming through the door - and I go up to him and say “General” and shake his hand and say “you haven’t changed a bit” He stands back and looks at me and laughs and says “Eddie, he says, you got really old!”

“Later I went to the john, and there’s a lot of graffiti on the wall “we know who you are, you fucker”. This past year he closed his place - nobody would go there. A friend of his in the CIA gave him money to buy it, but finally he just went out of business.

“Two people died in that photograph. The general killed the Viet Cong. And I killed the general with my camera.

“Now the general is dying of cancer (d. July 1988)

“I’ve been trying to get him to do a workshop up here, to talk about the picture, but he chickened out. Then I almost had him give a TV interview - you see, I’m trying think of some way of clearing his name. Right now I’m talking to a national magazine, but he doesn’t want to do it. In the meanwhile, I feel totally responsible for the abuse that’s happened to this man.

“I’ve been quoted several times as saying “If you were that man, at that time in history, and they grab this guy - who you know is an enemy - who’s killing your people, who has just machine gunned a load of kids in a kindergarten and killed his brother who was a local policeman, what would you have done?

“How do you know you wouldn’t have blown his fucking head off if you had the pistol? And because of a fluke, I just happened to be there at the right time and recorded what was in front of me.

“I’m labelled with that picture and I’m going to be labelled with it for the rest of my life - like an actor who gets labelled with a television series and can’t work as another character. I don’t want to be known for trying to escape a single image and yet I am - I’ve been trying to escape that fucking image for years.

“It’s going to be there for the rest of my life and that’s really spooky.”

Eddie felt so strongly about the mistreatment of war photographers and their work, that once a year he invites 72 exhausted photo journalists and photographers to his farm for a week of photography and anti-war conversation. Unknowingly his farm had become the location of therapy sessions long before therapy had become so accepted.

“Why 72? Because seventy-two photojournalists were killed during the Vietnam conflict trying to get their photographs into the public domain and show that things weren’t all that great.”

memorial to these deceased photographers, engraved with their names and had a fire pit just beside the barn. 72 seats made of stone in a circle with a fire pit in the middle where there these damaged photo journalists would get drunk, tell their stories and whinge about censorship that was prevalent in America at the time.

It's worse now.

The Vietnam War was the last time American government censors allowed photojournalists the freedom to cover any conflict as they saw fit and, of course, American magazine editors weren’t about to publish the negative side of the war anyway. So the pictures simply disappeared in amongst all the other censorship bullshit that has gone since that time.

Every aspect of conflicts since then (particularly the Iraq war) have been stage managed by the American government - particularly photography and TV. In reality, America has rewritten the history of all conflicts to be the history they want you to see.

While I was listening to Eddie Adams, and watching him play with the three-year old son playing at his feet, I realised that he had never really had the opportunity of playing childhood games with his infant children - he’d been away playing war games and missed his own children and grandchildren growing up.

As we walked from the kitchen, I had noticed, a large fabric sculpture of a couple of mushrooms in the hallway, I suggested we could make a child-like photograph of him in the snow seated under the mushroom.

Eddie took a bit of convincing, because in his genre of photography, you never ‘make a photograph’. You just simply record whatever is before you, with honesty. You ‘take’ rather than ‘make’ the image… but he warmed to the idea and as quickly as possible we set it up at the crest of a small hill in his backyard. It was then about 4.30 on the winter afternoon, and the light was failing.

In fact the light was so low the resulting negative has always been a bugger to print. And then it was over. We had the picture I wanted, the promise of a roaring log fire, removing the chill in our toes and the aroma of spaghetti sauce wafting into his back yard, enticed us back to the warmth of his cosy kitchen. It was a fabulous evening of conversation on photography and politics, red wine, crusty bread and spag boll.

It was an evening I will never forget.